Shan Fei Ming Solo Show

Opening:Feb.18th

Date: Feb 17th to Mar 30th

展览现场 On-site

展览现场 On-site

展览现场 On-site

展览现场 On-site

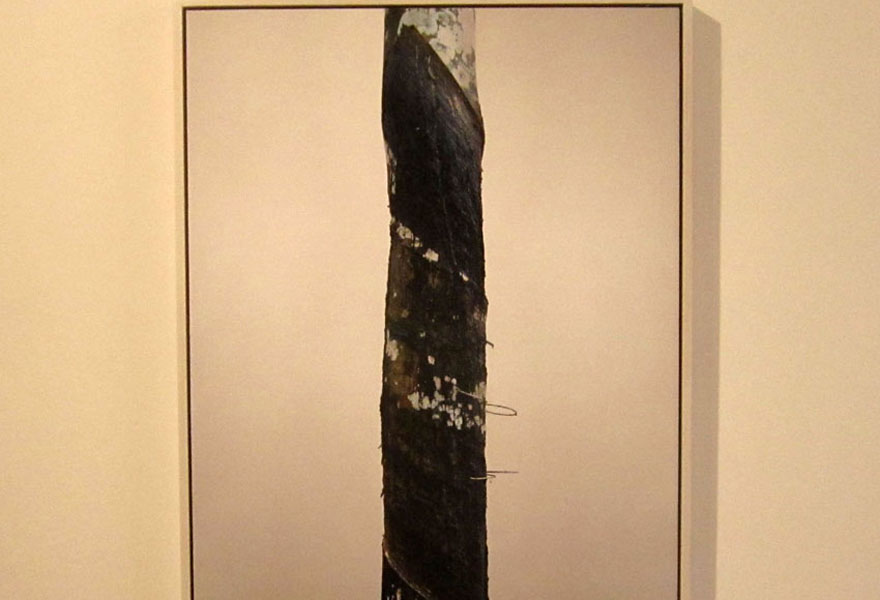

Tree Hole 树洞

树洞2.jpg

树洞1.jpg

Press Release

A Metaphor of the Tree

—On Shan Feiming’s Photography

Hantao Shi

I was introduced by my friend that artist Shan Feiming is an introverted yet determined young man, who studied traditional Chinese painting in his childhood and later went to study in Germany and majored in photography. Hence I felt it easy to comprehend his art, because I can find evidences of those descriptions from his photographs, for instance, his perception and depiction of simple objects, carefully-designed and simplified composition, accurate exposure and detailed presentation of each image, and so on; which can also be attributed to the influences and training he has received from both Eastern and Western art education. Also, that tiny and pale body, soaked in deep blue-green ocean, perfectly revealed his helplessness due to his frustration in love. All these foresights made me doubt whether I will get anything fresh from him when we meet. I am afraid that I would end up listening to a young artist’s self-addicted, art terminology-filled monologue, as I have experienced in numerous similar scenarios.

To my surprise, after our brief greetings upon my hustled arrival, he started to talk vigorously about the background based on which he makes his art. His frankness and honesty helped to eliminate the unfamiliarity caused by our short acquaintance, yet what surprised me more was that he was able to discuss and blend his art practice and social issues so naturally in his statement. He mentioned the exact time, venue and happenings when he shot each photo, and commented a variety of social maladies without hesitation, which was actually like long-reserved comments rushing out from his heart. I learned later that I am five years older than Shan Feiming, we went abroad in the same year in 2006 and both moved back to China in 2010 (we never heard of each other before, plus we were thousands of kilometers away). Interestingly enough, in these four years, a myriad of unprecedented social ills seemed to explode in China. As two young Chinese expatriates who were newly granted access to massive information, we shared similar shocks and feelings. Just like what he said, I felt the first time in my life that I am so close to my country and my people, thousands of voices and opinions flooded to me at the same time… (I) was able to overlook all previously shielded truths. I also remembered those reborn-like shock and dumbfounded feelings. In the end, I had to admit that we were meant to meet and get to know each other, not to mention that we also share the interest of photography.

Although we became friends immediately after our first met, I was bewildered by his art: What has transformed those strong feelings and concerns into such calm and delicate pictures? How can he turned to the wild and used his camera to capture trees and shadows, clouds and mists, when he cares so deeply and genuinely about the contemporary society? What can we perceive between his questing of these social realities and his art?

Shan Feiming mentioned his motives in his talk and written statement. According to him, Rubber Tree tried to discuss “the alienation in today’s China, from the ecosystem to food safety to social morals…, which is certainly not to criticize rubber industry, but to draw a metaphor from those lynched-like, layered-peeling scars of rubber trees. While the shooting of Nycticebus Pygmaeus was perhaps inspired by his favorite artist, Hiroshi Sugimoto; the image of those caged lively monkeys finally disappeared after a long exposure, through which Shan attempted to signify the neglect of life by authority, and the nullification of life with no reasons. The creation of Tree Hole series seemed to be driven by subconscious; it is only after the shooting completed, he realized that he has seen this metaphor in a movie, which said that tree holes are where people spit their secrets: talk the secrets, then seal the hole with mud. However, I am not sure whether this action symbolizes remembrance or oblivion. Jungle series drastically differs from other work; every picture is filled with great details, airtight. Shan said he was inspired by the mist of the mountain area in Yunnan province, which can be seen as a depiction of unforeseeable future.

Viewers’ first impression of Shan’s photography make them believe his art is introvert, and without knowing the background and motivation, they can hardly grasp the artist’s intention. Shan’s narration not only disclosed his feelings and thoughts, but the meaning of his artwork; we can also detect the coherent yet paradoxical approaches he applied in his various series; one of those approaches is metaphor. In fact, every piece of good photography work is more or less metaphorical; according to the renowned linguist, George Lakoff, "Our ordinary conceptual system, in terms of which we both think and act, is fundamentally metaphorical in nature." Apart from a fundamental depiction of physical objects, all languages are including metaphors. While each photo, as a slice of time, records the photographer and the viewer's cognition of a broader social event, as well as their communication; therefore, metaphor is one of the basic rhetorical approaches of photography.

Nevertheless, in most photography works, metaphorical object is a part of the subject. For instance, in artist Lu Yuanmin’s work, those cramped urban spaces or uneasy gestures indicated the modern city and its habitants’ life and emotions. Also, in Luo Yongjin’s collage or Liang Yongliang’s landscape scrolls, there are hidden urban structures, which came from fragments of urban scenes, composed the picture, and finally pointed back to the same urban reality. If interpreted from photography semiotics perspective, each photo can be seen as an index: no matter what restrains the photographers during the process of shooting or what limitation the objects have, a photo at least recorded an object or scene that has existed in a certain space and time. Therefore, this index becomes a clue through which viewers can trace back to the photographer’s intention. Interestingly, Shan’s metaphor seems to be jumping or non consecutive (from the entire meaning circle). Often he signifies a number of social issues through depicting a natural or pseudo-natural object or landscape. Hence when he shot the Monkeys series, he showed no monkeys in final pictures; and when he gazed the rubber trees, he saw them no longer trees. We can be certain, every single piece of his photography did come from nature; however, there is no real nature in his photo, at least not the one he cares or signifies.

There are other photographers whose art signifies meanings beyond the surface, such as the empty landscapes in Cai Weidong and Lu Yanpeng’s work, or the images of Zoos in Lu Yanjin and Chang He’s work, which would create an atmosphere by adjusting tunes and shadows and navigating compositions and layouts, rather than merely capture actual landscapes or objects, in order to comprehensively deliver the perception and mood of an individual or a group of people; in their art, these artists build a bridge that links forms, aesthetics, and emotions. Yet Shan Feiming went further in his photography; he used even more abstract vocabulary to represent concrete yet fine objects; however, signified more specific social problems and events. His approach seems to be closer to Lakoff’s definition of metaphors: using existed knowledge in one field to provide new perception and interpretation channels for another field’s knowledge. It is also this distance between the metaphorical objects and subjects, especially the artist’s interest in nature that makes me refer to another feature of his art, which is, an evasion from realistic styles. I believe this is influenced by his training in traditional Chinese painting.

We have to admit, no matter how deeply Shan Feiming concerns about this society, we can no longer find any social life in his works, nor can we see any real people. This challenges our usual definition of photography. Because of the recording and representing nature of photography, we are used to its primary function of observing our exterior world; once we press the shutter button, we capture our perception and comments of the objects in a picture. Shan Feiming’s motivation comes from all sorts of social realities, yet he only expresses his concerns about the society when he faces natural objects, and tries to depict those natural or pseudo-natural objects. His photography differs from early pictorialists’ seeking classical aesthetics, and does not attempt to evoke hypocritical feelings by sublimating and ennobling natural landscapes like landscape photographers do. To Shan Feiming, photography is his individual narration of fables, an abreaction of emotions, or even, an escape from current social realities. This gesture coincidentally agrees with Chinese literati paintings' attitudes and aesthetics. For instance, Yi is an important aesthetic criterion that guided generations of literati paintings; it is about exceeding current social problems and realities. No matter to escape from tangled wars in Song, Yuan and the Five Dynasties, or to survive from the combats between Ming and Qing Dynasties, artists chose to live in seclusion in the mountains and paint Shanshui (mountains and waters) in long scrolls; even renowned scholars and intellectuals would like to express their emotions in Shanshui, landscape painting. The literati artists, either senior officials or intellectuals, cared and concerned about the human society; some were even ambitious of social reform, yet once their philosophy of life confronted the harsh realities, it was always Shanshui the place that their soul would reside.

Also, Shan’s precisely depicting simple objects resembles literati artists’ obsession of the rhythm and pace of ink and brushworks. Chinese literati painting focused on capturing the spirit of nature, rather than realistically depicting it. The artists applied ink and brushworks playfully, through which they expressed their inner self; hence the ink and brushworks carried and conceived artists’ emotions,and finally developed to a typical aesthetics value system. From his work, we can perceive Shan Feiming’s employment of advanced photography techniques, his intensive observation of ordinary objects, such as trunks and leaves, which breath vividly in his picture with their details, and his obsession on these objects he shoots. Without knowing the artist’s motivation, the viewers can also greatly enjoy these images. I am not saying that Shan Feiming merely addicts in techniques and skills, or seeks formalism aesthetics; I am not even saying that he truly indulges himself in nature. Yet his interest in landscapes, pine trees and bamboos, reveals his identity, a native of the Southern Yangtze area, which is also the hometown of numerous literati artists. Nevertheless, Shan Feiming’s art is absolutely irrelevant to the tradition of Chinese ink painting’s brushworks; we can only tell that he employs the metaphoric approaches of traditional Chinese painting in his photography.

Shan Feiming’s photography is unique among Chinese photographers. As mentioned before, his art practice and experience, together with his photography skills, gave his work a free and natural look; yet meanwhile, what underneath the pictures are metaphors about his caring of this society. His art is a product produced by a young Chinese artist whose cultural background and the contemporary realities have deeply intertwined in his heart; and the works have betrayed a disturbing nature of struggling between his interiority and exteriority, as well as the hybrid from the East and West.

replica handbags online, cheap replica designer handbags, cheap replica handbags replica handbags

Artists